Why businesses need to finance the SDGs

Launched in 2015 and adopted by all 193 UN-member countries, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs, or Global Goals) have set the world on a pathway to achieve a set of goals and targets by 2030.

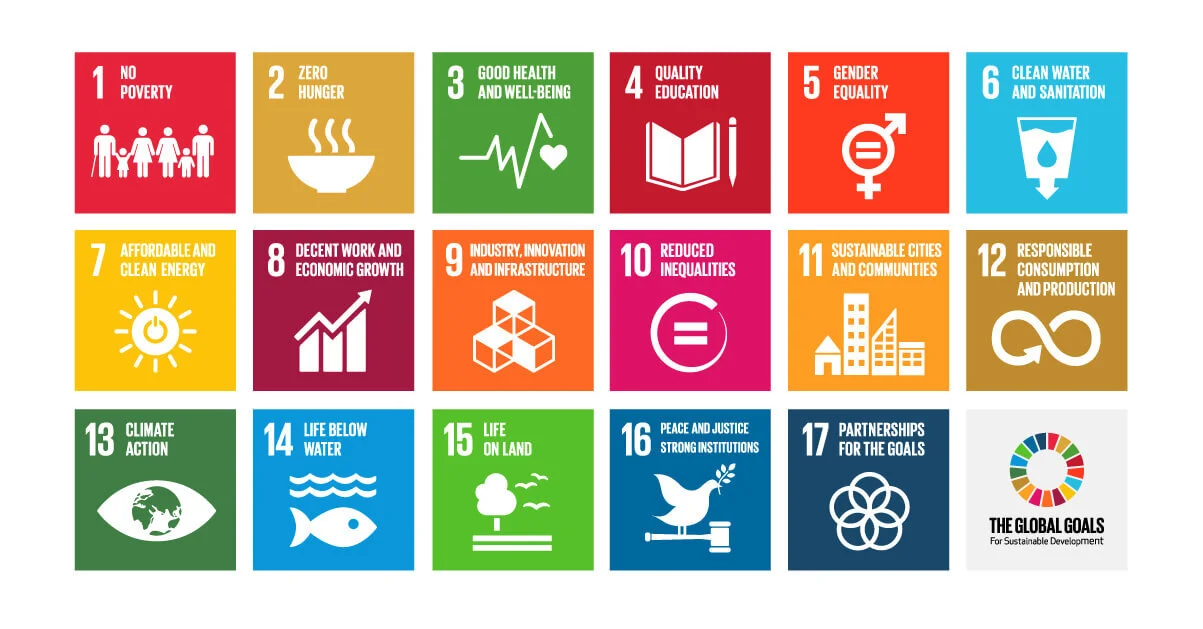

With 169 targets grouped into 17 goals, the SDGs aim to end poverty, tackle environmental challenges, and enhance human development through innovation, to name a few. In achieving these goals and targets, businesses can expect to benefit enormously too. So far so good, right?

The current estimate for the financing the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) stands at US$2-3 trillion per year, yet only a fraction of this has been made available two years since their launch, representing a huge shortfall. Nonetheless, there are continued signs of growth, with HSBC’s recent US$1 billion “SGD Bond”, designed to support projects across seven of the SDGs, being three times over-subscribed.

So how do we ensure they have adequate financing, and ultimately their success? TPB’s founder and director, Pat Dwyer, chaired a panel of wide-ranging experts at a recent seminar held by TPB and the British Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong, and hosted at the British Council.

Through the eyes of financiers

An area that has caught a lot of media attention recently is impact investments: those with the intention to generate environmental and social benefits alongside a financial return. According to James Gifford, Senior Impact Investing Strategist at UBS, a key concept here is additionality, defined as “the additional environmental and social impact created as a result of the investment, which would not have otherwise taken place via conventional routes”. Because of their additional and intentional benefits, impact investments, whether at the fund or company level, are set to play a key role to achieving the SDGs.

But this is as yet no easy task. The nature of impact investments means they are often found in relatively illiquid markets (i.e. not readily convertible to cash), whether small-scale projects or in developing countries. In liquid markets, this is often limited to shareholder engagement. For impact investments to scale to the mainstream, James believes it is critical to demonstrate upfront to investors their environmental and social benefits, as well as their commercial viability. A key challenge the market therefore needs to overcome is the measurement of the non-financial indicators involved.

Another area of significant growth is in green bonds. This is particularly notable in China, which went from almost zero issuance prior to 2016 to US$36 billion, or 40% of all green bonds issued in 2016, according to Chaoni Huang, Director of Green and Sustainable Solutions at Natixis. In order to meet China’s environmental targets (with the main focus areas being renewable projects, pollution control, infrastructure and decent work), the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) forecasts expects 85% of the US$1 trillion needs to come from the private sector. One challenge, however, is transparency around the use of proceeds and impact reporting, despite PBOC’s stringent regulations. As transparency improves, and with the backdrop of China’s commitment to the SDGs, the Paris Agreement, and climate/energy targets in its 13th Five Year Plan, green bonds are set to continue to play a crucial role in financing SDGs in the foreseeable future.

Panel: the SDGs, a US$3 trillion per year opportunity (The Purpose Business)

Through the eyes of corporates

The corporate perspective is not too different either. For Janice Lao, Director of Corporate Responsibility and Sustainability at The Hongkong and Shanghai Hotels, Limited (HSH), it is absolutely critical for the business to understand where it would make the greatest impact before selecting which SDGs to align with. As a business that has been around for over 150 years, creating positive impact has been in the DNA of HSH and the Kadoorie family behind the hotel group. As Janice explained, the key to creating this positive impact is by having a clear sustainability vision and strategy, i.e. something that the business is living and breathing already anyway, and mapped to the SDG framework. Then, by virtue of this integrated thinking, any financial activity – whether investors of the business, or projects financed by the business – would be impactful and contribute to the SDGs in question.

She also gave us some insights from her former management role at MTR, which issued one of Hong Kong’s first green bonds in November 2016, worth US$600 million. Being 75% owned by the Hong Kong government, the green bond issuance was initiated and driven by the government. Whilst this was perhaps a good example of shareholder activism, there is still much more that the private sector in Hong Kong can do even without government support – indeed a challenge in Hong Kong faces not only in the green bond arena, but in the wider sustainable finance market too.

Through the eyes (and legs) of the activist/NGO

For Mina Guli, founder and director of Thirst, educating people and raising awareness of the SDGs is still a challenge. She focuses on raising money to spread the word, specifically in one SDG that she passionately believes that everyone should care about: SDG 6 – clean water and sanitation. SDG 6 is critical because water fundamentally touches on every aspect of all our lives, all across the world. Once businesses understand the scale and pervasiveness of water-related challenges, risks and adverse impacts on business operations, financing for tackling these would naturally follow.

Mina has therefore made it her mission to raise awareness for SDG 6 amongst business leaders around the world. How? Apart from impassioned storytelling, she also attracts a fantastic amount of media attention and corporate partnerships from her “7 deserts run” and “6 river run” in the last two years (equivalent to a combined total of 80 marathons), as well as an upcoming 100 marathons in 100 days in 2018. So by raising awareness amongst the world’s largest corporates, their subsequent actions to tackle water are expected to have an enormous impact on their global supply chains, and their financing becomes much more straightforward and part and parcel of everyday activities.

Conclusion

With such a large shortfall of financing for the SDGs, there are clearly opportunities for the private sector to seize upon. As we have heard from the panel, financing the SDGs comes in many forms – from impact investing where the investor receives both a financial and social/environmental return, to embedding SDGs into the core of a business so as to address key risks. The first key step, as echoed by the panel and audience, has to be education and awareness amongst businesses and investors, so that they understand the gravity, impact and scale of the issues as well as potential opportunities. Achieving the SDGs is not only about “doing good” for the world, it is also critical for any business wishing to thrive in the future.